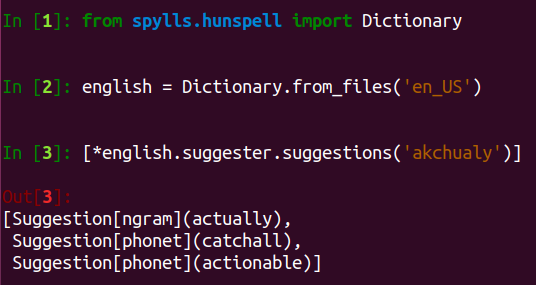

Rebuilding the spellchecker: Well, akchualy...

This is a part of the ongoing “Rebuilding the spellchecker” series, dedicated to explaining how the world’s most popular spellchecker Hunspell works, via its Python port called Spylls. You can start reading from the first part (or look into the series TOC), but this is not a requirement: I provide here all the necessary context to follow this article.

In the heart of every spellchecker is the algorithm for suggesting corrections, called just suggest in Hunspell. Ideally, it should provide a list of suggestions that is comprehensive yet concise, trying hard not to miss the right suggestion for a severely misspelled word, and at the same time not to overwhelm the user with too many variants.

As we’ve seen in the suggest overview, the task is not only complicated, but also it doesn’t have a singular right answer, and the quality of the solution is quite hard to estimate objectively.

Full dictionary search

The previous part demonstrates Hunspell’s approach to simple misspellings: it generates a list of “edits” (like inserting one letter, removing one letter, and so on), and tries to find out whether some of them are correct dictionary words. Too often, though, it is not enough: all corrections found via edits are one or two characters different from the misspelling, so the search space is limited. In real life, even the accidental typos of the perfectly educated writer will not always be possible to correct this way. If we consider genuine spelling mistakes, we’ll see a wide range of possibilities for how severely a word can be corrupted while still staying recognizable to the human reader.

When all attempts to generate suggestions based on edits have failed, Hunspell uses another strategy: just stop guessing and search for similar words through the entire dictionary.

Those who follow the series long enough might remember that we have a problem here: there is no complete list of all possible words. Hunspell’s dictionary is a list of stems and affixes that can be attached to them. Iterating through all possible word forms is computationally expensive—not even mentioning the problem of iterating through compound words… because the lookup through entire dictionary ignores them completely.

Another problem is how to estimate the similarity of suggestion to a misspelling so it will be aligned with the user’s intuitive understanding. Hunspell uses two approaches (the first one much more often): lexicographical, or n-gram-based similarity; and phonetic similarity.

N-gram similarity: beautifully ad-hoc

For a full-dictionary similarity search, Hunspell first needs to handle the problem of the efficient iteration through the list of possible word forms. Producing them all on the fly is unrealistic performance-wise, so when the n-gram similarity is used, Hunspell (and Spylls) acts this way:

- Iterate through all the stems and find 100 of them most similar to a misspelled word (with rough-and-quick scoring formula)

- For those 100 stems, generate all possible affix forms and find 200 of them most similar to a misspelled word (with another rough-and-quick scoring formula)

- Calculate a very sophisticated similarity score for those 200 chosen forms

- Sort by the final score, and return the best ones (up to 4)

This “funneling” approach—first choosing stems, and then only looking at forms of those stems—means that the whole algorithm is only suitable for dictionaries with long stems and short affixes (where “misspelled word is similar to a stem” = “misspelled word is similar to most of the word”). This assumptions is wrong, for example, for Korean (very short words), or Brazilian Portuguese (“longuissimamente” = “longo” + “uissimamente”).

Scoring formulae are based on n-gram counting (though there are more components to each formula). Thus, Hunspell (and Spylls) colloquially refer to this stage of suggestion algorithm as “n-gram search” or “n-gram suggest”. It is just counting n-letter combinations that are common for two different words: the higher the score, the more they are similar. For example:

from spylls.hunspell.algo.string_metrics import ngram

ngram(3, 'actually', 'akchualy') # n is up to 3

# 11 = a, c, u, a, l, l, y, ua, al, ly, ual

ngram(3, 'actually', 'akshuly')

# 6 = a, u, a, l, l, y, ly

The full scoring formulae, though, use not only n-gram counting but several other lexicographical metrics—and are, if I may say, beautifully ad-hoc. It seems that they were grown through years of trial-and-experimentation to choose the coefficients and the order of summands—not related to any theoretical linguistic meaning but just found empirically. Those parts of the algorithms strongly resemble how machine learning works; only, in this case, it were Hunspell developers who adjusted “weights” after each evaluation. ML analogy is an interesting topic that we’ll investigate in one of the later chapters.

Just to have a taste of it: the detailed similarity score of step 3 is calculated based on:

- the longest common substring length of the misspelled word and candidate;

- leftmost common substring length;

- the number of same characters in same positions;

- ngram score with N=4;

- and weighted ngram score (absent ngrams add negative points) with N=2.

It also adds a reward for words with long common substring (putting the candidate in the “very good” bag), and a penalty based on too low 2-gram score and

MAXDIFFsetting of aff-file (typically putting the candidate in the “very questionable” bag).For those more in favor of formal descriptions,

ngram_suggest.precise_affix_scorecode provides one.And the

ngram_suggest.ngram_suggestmethod gives a full definition of the algorithm.

The math typically pays off:

print(*english.suggest('procudur'))

# procedure

# ...

print(*english.suggest('madnifisent'))

# magnificent

# ...

…but some unexpected results are also quite possible:

print(english.suggester.suggestions('rielistik'))

# Suggestion[ngram](Kristie) # The first ones feel "just wrong" for a human :(

# Suggestion[ngram](Christlike)

# Suggestion[ngram](relist)

# Suggestion[ngram](Listerine)

# Suggestion[phonet](realistic) # Oh, here we are -- phonetic suggestion

# Suggestion[phonet](moralistic)

The last example brings us to…

Phonetic similarity: useful yet unused

The “rielistik” example shows a very typical spelling error of a child or non-native language user: the word is spelled close to its remembered pronunciation. Correcting this class of errors requires understanding of the phonetic similarity of two lexicographically different words. It is an important feature of a spellchecker—and Hunspell actually implements it… But it so happens that almost no Hunspell user can make use of it. We’ll discuss the reason in a few paragraphs, but first, let’s see how it works.

Phonetic similarity suggestion, like the n-gram-based suggestion, is performed via a full dictionary search. But the similarity is calculated between metaphones codes of misspelled word and each stem, instead of their literal values. Metaphone is defined in Wikipedia as “a phonetic algorithm […] for indexing words by their English pronunciation”: it is a way of converting words into such representation (metaphone code) that similarly-pronounced words have same or similar representations.

from spylls.hunspell.algo.phonet_suggest import metaphone

print(metaphone(english.aff.PHONE, 'rielistik'))

# RLSTK

print(metaphone(english.aff.PHONE, 'realistic'))

# RLSTK

Note that metaphone (which is the method used by phonetic suggest internally) needs data from aff-file. PHONE directive stores the table of phonetic equivalence in quite complicated format, which was initially designed for aspell spellchecker. Hunspell is an international product, so it can’t include the data for language-specific algorithms in its code and transfers the responsibility of providing it to the dictionary authors.

And here lies the first problem of the phonetic suggestions: of all LibreOffice and Firefox dictionaries I’ve checked, only one has PHONE table defined, namely, en_ZA (South African English). Even other English dictionaries—American, British, Canadian, etc.—don’t use this table for reasons that are a mystery for me (but the table is definitely not SA-English specific). I am also not aware of any attempt to create a PHONE-table for languages other than English, though there are several pronunciation-encoding algorithms. Many are multi-lingual or designed for languages other than English (for example, abydos Python package lists and implements two dozens of state-of-the-art ones).

Note: The

en_USdictionary that is distributed with Spylls and used for examples in this article is a Frankenstein made from the latest dictionary from the SCOWL project (it doesn’t havePHONE), plusPHONEtable from the dictionary stored on Hunspell’s site which is recommended by Hunspell for suggestion quality testing (the README says it is OpenOffice dictionary from 2007).

The second problem with Hunspell’s implementation is that, unlike n-gram-based suggestion search, it iterates only through root stems. E.g., no word with suffix or prefix would ever be found this way, significantly limiting the probability of a relevant suggestion.

Akchualy, I had to spend some time to find the misspelling of “actually” for this article’s title: most of the others wouldn’t have “actually” in a list of suggestions. The phonetic suggestion could’ve solved the issues (as all misspellings have metaphones very similar to the correct word):

print([metaphone(english.aff.PHONE, word)

for word in ['actually', 'akshually', 'akchualy', 'akshully']])

# ['*KTL', '*KXL', '*KXL', '*KXL']

…but the expected suggestion isn’t provided by Hunspell (or Spylls):

print(*english.suggester.suggestions('akshually'))

# Suggestion[ngram](squally)

# Suggestion[phonet](eggshell)

# Suggestion[phonet](catchall)

…because stem “actual” + suffix “ly” will never be considered by phonetic suggest. The same is true for, say, the word “excersized” (made famous by the article comparing Hunspell with Aspell): it is phonetically similar to the (correct) “exercised”, but being stem+suffix, will never be found.

It looks like this important spellchecker feature fell into a negative feedback loop: its Hunspell implementation is so limited that nobody asks for implementation improvements (because no dictionaries need it!), and no dictionary authors add definitions to their dictionaries (because it is hard, and no other dictionary has it, and the suggestions would still be sub-par).

On this sad note, let’s wrap it all up!

Spyll’s reimplementation of the phonetic suggest can be found in

phonet_suggestmodule. I should warn, though, that it cuts some corners in supporting the full format of the definition described by aspell—because it is not that “core” algorithm in Hunspell, and there are plenty of high-quality implementations for metaphone and other phonetic encoding algorithms. Spyll’s implementation still passes Hunspell’s tests, though, and seems to work as expected with that EnglishPHONEtable.

Suggest: takeout

Let’s zoom out a little and see what we now know about implementing the suggestions for misspellings—at least about the way Hunspell does it:

- Finding the corrections for a misspelled word is a non-trivial task; finding the corrections that would look meaningful for the human—ten times more so.

- There are three base approaches to suggest: edit the misspelled word and see if it will produce a good word; look through the entire dictionary and find most similar words; look through the table of known misspellings and check if the provided word is there. Hunspell uses all three (the third one via

REPtable if it is present in aff-file of the dictionary, on the edit stage). - There is no single state-of-the-art algorithm, neither single all-consuming lexicographical formula to “solve” the suggestion search; the (relatively) decent quality of Hunspell’s suggestion is achieved by a rigid combination of simple algorithms and calculations developed through many years.

- Phonetical similarity is important for suggestion search but is virtually unused by the Hunspell.

Together with word lookup description (“Just look in the dictionary, they said! “, “Compounds and solutions”), this covers most of the Hunspell’s core algorithms. The quality of spellchecking is defined by these algorithms and how the dictionaries are built and maintained—which, as everything about Hunspell, is a problem with a ton of nuances, edge cases, and unfortunate implementation details. We’ll see it in the next chapter.

Follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list if you don’t want to miss the follow-up!